Task Force 4: Refuelling Growth: Clean Energy and Green Transitions

A growing number of G20 countries are committing to more ambitious greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction targets to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5ºC, which is needed to prevent catastrophic climate change. Yet, achieving these climate objectives will be a massive challenge as coal remains a substantial source of fuel for the energy sector, employment and incomes in developing G20 countries. The transition towards a carbon-neutral economy may have negative labour and social consequences, particularly for those along the coal supply chain. It is important to minimise the potential negative socioeconomic consequences, such as job losses. To ensure a ‘just’ transition, this Policy Brief recommends that the G20 develop a common guidance for member countries, which can also be called principles or best practices. The G20 can prepare this jointly with the G7, multilateral development banks (MDBs), and think tanks.

1. The Challenge

1.1 Energy transition

A growing number of countries in the G20 are committing to more ambitious carbon reduction targets to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5ºC; this is needed to arrest the existential crisis of climate change. Developing countries from the G20, such as Indonesia, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), South Africa, and Saudi Arabia, have pledged to move to net-zero carbon emissions by around 2050–2060.

Meeting the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) is needed not only for restricting the global temperature rise to 1.5ºC to avoid catastrophic climate change, but also for local benefits. Apart from global objectives, NDCs have local benefits. Examples of local benefits from energy transition include:

- reduction in air pollution (fossil fuel is a significant source of air pollution, which is hazardous to human health due to both outdoor and indoor air pollution);

- energy security (a recent fossil fuel price increase challenged energy security, in addition to underlining the fact that fossil fuels are exhaustible resources); and

- generation of employment, such as quality green jobs.

Fossil fuel is a significant source of emissions. Coal is a highly polluting fossil fuel. Pollution is especially high from unabated coal-fired power plants without pollution reduction technologies, such as carbon capture and storage. A quarter of global emissions come from coal-fired power plants. Efforts for reducing emissions from coal-fired power plants include the following:

a) Stop new

Many countries and organisations have pledged to end new unabated coal-fired power plants in the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement at COP 26. Many MDBs have committed to stopping financial support for new coal-based power plants.

b) Retire existing

For accelerating the phase-out of unabated coal power generation, financing is vital as existing coal-based power plants cannot be simply shut down; they need to be replaced with low-carbon energy supply, such as renewable energy and energy storage.

c) Remove fossil fuel subsidies

Ineffective/non-targeted fossil fuel subsidies are heavily criticised for their economic inefficiency; “… although designed in the interests of the poor, they typically benefit medium- to high-income households, which are bigger energy consumers.”[1]

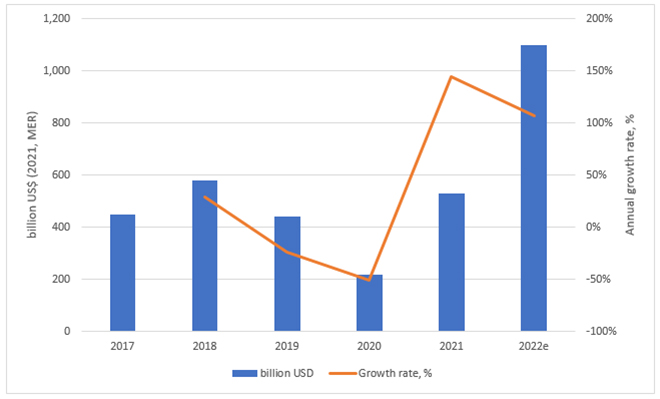

Also, they are a burden to public expenditure: fossil fuel subsidies in India and Indonesia, for example, are extensive, amounting to almost 8 and 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), respectively, in 2020.[2] G20 countries have committed to phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support for the poorest.[3]However, high inflation resulting from the war in Ukraine, including in energy, made climate pledges even more difficult to implement without resulting in increased energy poverty and energy insecurity. Fossil fuel subsidies nearly doubled in 2022 compared to the previous year (Figure 1). The subsidies are primarily concentrated in emerging market and developing economies.[4]

Figure 1: Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Source: Author’s own, using data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), 2022

Note: 2022e – 2022 estimate

1.2 ‘Just’ transition

Achieving climate objectives is a massive challenge for countries where fossil fuel remains a significant source of energy, income, and employment. Energy transition may have negative labour and social consequences, particularly for those along the dominant fossil fuel (such as coal) supply chain. Jobs in coal supply and coal‐fired power generation account for around 0.25 percent of the total global employment, but it is more worrying for communities that are highly dependent on income generated from the coal industry. Coal employment is concentrated in Asia—mainly in three countries—with 3.4 million coal workers in the People’s Republic of China, 1.4 million workers in India, and around 470,000 workers in Indonesia.[5]

Countries, provinces, and communities depend on fossil fuel as it is a source of energy; people also rely on the income and employment associated with fossil fuel extraction. Ensuring a transition that is ‘just’ is especially important in such provinces and communities. For example, coal contributes 35 percent of GDP and employs nine percent of the population in East Kalimantan in Indonesia.[6] Thus, it is important to protect and support vulnerable communities, industries, and workers.

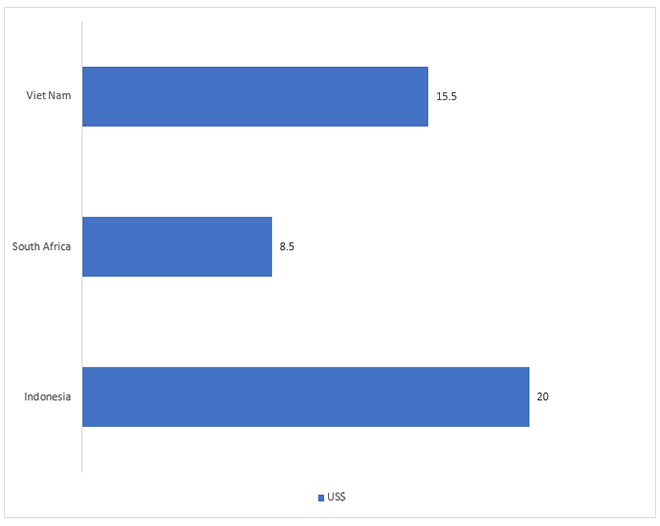

The International Partners Group (IPG), which includes the Governments of Japan, the United States, Canada, Denmark, the European Union, Germany, France, Norway, Italy, and the United Kingdom, and MDBs recognise the importance of ‘just’ transition. The IPG defines just energy transition as an energy transition “that brings about opportunities for industrial innovation to create quality green jobs and considers all communities and societal groups affected directly or indirectly by an expedited reduction of power sector emissions through early retirement of coal-fired power plants – including women, youth, and others vulnerable to the transition.”[7] The Just Energy Transition Programme (JETP) is a financing mechanism, launched by IPG countries, for accelerating the phase-out of unabated coal-based power plants and the scaling-up of lower-emission technologies in emerging economies as well as for supporting workers and communities that are coal-dependent.

Figure 2: Just Energy Transition Partnership Funding (2021–2022)

Source: Author’s own

2. The G20’s Role

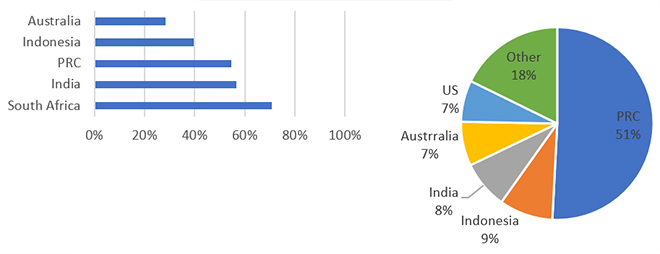

The G20 includes top coal consumers and coal-intensive countries (Figure 3). Thus, just energy transition issues are highly relevant to the grouping. It has been working on JETP in partnership with the G7 countries (which agreed to Joining Forces to Accelerate Clean and Just Transition towards Climate Neutrality).[8] With a few G20 members, i.e. India, Indonesia, and South Africa, having already joined JETP, the forum can contribute to the acceleration of energy transition that is just in other countries and regions. The G20 can continue to work with the G7[9] and multilateral development banks to share best practices for ensuring just transition. This will help promote just transition in other G20 member countries, attract investors, and gain public acceptance.

Figure 3: Top Coal Consumers and Producers in the G20

|

|

| a) Top five coal-intensive G20 countries in 2021 (by primary energy consumption) | b) Top coal producers, percentage share of global production in 2021 |

Source: Author’s own, using data from British Petroleum[10]

3. Recommendations to the G20

Just transition should be at the heart of energy transition programmes. Countries need to ensure that energy transition is just, especially for low-income and vulnerable groups. Half of the most coal-dependent countries have coal phase-out targets, but very few have relevant just transition policies.[11] This Policy Brief outlines recommendations to reduce the negative side-effects of energy transition, to be planned along with energy transition in affected provinces, communities, and sectors. The main recommendation is for the G20 to develop the G20 Just Energy Transition Guidance (or principles or best practices; hereafter, Guidance).

Proposal: The G20 Just Energy Transition Guidance

The G20 can develop a Guidance for countries for promoting just energy transition. This Guidance will be particularly useful for countries working on energy transition. This can be developed by the G20 jointly with the G7, multilateral development banks, and think tanks. Following this Guidance will not only allow countries to better plan just transition, but it will also promote public acceptance and attract investors.

A similar document is developed by multilateral development banks; it is called ‘MDB Just Transition High-Level Principles.’[12] The objectives of this document are to articulate a common understanding of MDBs’ support for just transition and to guide their policies and activities. This was jointly developed by nine MDBs: ADB, AFDB, AIIB, AIIB, EBRD, EIB, IDB, IsDB, and NDB.[a] It provides five principles of just transition, agreed upon by the MDBs.

The five high-level principles state that low-carbon transition support will be provided in the following way:

- enabling socioeconomic outcomes;

- ensuring that financing, policy engagement, technical advice, and knowledge sharing are in line with MDB mandates and strategies, and country priorities, including NDCs and long-term strategies;

- building on existing MDB policies and activities, mobilising other sources of public and private finance, and enhancing coordination through strategic plans that aim to deliver long-term, structural economic transformation;

- mitigating negative socioeconomic impact and increasing opportunities, supporting affected workers and communities, and enhancing access to sustainable, inclusive, and resilient livelihoods;

- and ensuring transparent and inclusive planning, implementation, and monitoring processes that involve all relevant stakeholders and affected groups, and further inclusion and gender equality.

Other references for developing the G20 Just Energy Transition Guidance include Joint Statements on JETP with Indonesia,[13] South Africa,[14] and Viet Nam.[15] G20 countries will benefit from similar guidance (or principles) on just energy transition. Currently, a common document for G20 countries on just energy transition does not exist. The Guidance (or principles or best practices) should include the following with regard to just transition:

i) Human Development

Just energy transition should include human capital development programmes through re-skilling, re-training, upskilling, and re-employment so that workers and communities, particularly those most affected by an energy transition away from such fossil fuel as coal, reap benefits. Countries should produce a plan for the above with a focus on women, youth, and vulnerable groups, earning a living in the coal industry or holding down jobs connected with the dominant fossil fuel. The necessity of a just, equitable and inclusive transition for workers and affected communities is emphasised by G7.[16] The above means that workers and affected communities are protected against the risks and can benefit from the opportunities. Examples of measures in this regard include:

- re-training workers employed in coal power plants and coal extraction;

- re-employment of workers who lost their jobs due to coal phase-out (coal power plant or coal extraction);

- repurposing coal power plants and coal extraction; and

- alleviating energy poverty.

ii) Financing

The measures mentioned above require financing. Funds should be planned so that they can be allocated for supporting the human development strategy. The amount of funds required will vary across countries and provinces, depending on their reliance on coal. Research institutions, including think tanks, should be involved to help with estimating the funds that are necessary and assessing the impact of transition, such as the burden on public expenditure for social security (e.g. unemployment benefits), which can increase due to energy transition.

iii) Transparency and Accountability

To make such efforts transparent and accountable, countries should establish an online platform. Such actions will also promote public acceptance of the coal phase-out and attract more investors. Phasing out fossil fuel needs trust and strong support from local populations through their confidence in the fairness of transition. Similar platforms have been started in Indonesia and Egypt. Such online platforms are trying to make energy transition transparent and visible. For instance, Indonesia has the ETM platform, launched in November 2022. ADB also launched its Just Transition Support Platform in November 2022.

iv) Organisation

Establish a local organisation, which will assist the government in its commitments to just energy transition and manage its day-to-day implementation in the country concerned. For example, Indonesia’s Secretariat for the Just Energy Transition Partnership was launched in 2023 for coordinating with internal and external stakeholders for the JETP, and for planning and developing projects for the JETP.

v) Knowledge Sharing

Sharing knowledge of the lessons learnt with regard to ensuring just energy transition is important for scaling it up in other countries and regions. ThinkTwenty (T20) and research institutions, including think thanks, can assist in this regard.

Attribution: Dina Azhgaliyeva, “Financing Just Energy Transition,” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023.

Endnotes

[a] ADB – Asian Development Bank, AFDB – African Development Bank, AIIB – Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, EBRD – European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, EIB – European Investment Bank, IDB – Inter-American Development Bank, IsDB – Islamic Development Bank, and NDB – New Development Bank.

[1] Asian Development Bank, Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Asia: Trends, Impacts, and Reforms – Integrative Report (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2016), xiii.

[2] International Monetary Fund, Still Not Getting Energy Prices Right: A Global and Country Update of Fossil Fuel Subsidies (IMF, 2021).

[3] International Energy Agency and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Update on recent progress in reform of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption (Toyama: IEA and OECD, 2019).

[4] International Energy Agency, Coal in Net Zero Transitions: Strategies for Rapid, Secure and People-Centered Change (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2022).

[5] International Energy Agency, Coal in Net Zero.

[6] “Indonesia’s Tilt at King Coal,” The Economist, last modified November 16, 2022.

[7] “G7 Chair’s Summary: Joining Forces to Accelerate Clean and Just Transition Towards Climate Neutrality,” G7-Germany, last modified June 27, 2022.

[8] G7-Germany, “G7 Chair’s Summary.”

[9] Venkatachalam Anbumozhi, Edo Aulia Aprihans, Dina Azhgaliyeva, Aaina Dutta, Shanti Jagannathan, and Zhanna Kapsalyamova, Accelerating “Just” Energy Transition: Implementation and Financing Pathways for the G7 (Tokyo: Think7 Japan, 2023).

[10] BP, BP Statistical Review of World Energy (London: BP, 2022).

[11] International Energy Agency, Coal in Net Zero.

[12] African Development Bank Group, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Council of Europe Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, IDB Group, Islamic Development Bank, and New Development Bank, MDB Just Transition High-Level Principles (Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, 2021).

[13] G7-Germany, “G7 Chair’s Summary.”

[14] European Commission, Joint Statement: South Africa Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (Brussels: European Commission, 2022).

[15] European Commission, Joint Statement.

[16] G7-Germany, “G7 Chair’s Summary.”