Abstract

Africa’s long-standing and difficult history with international capital can be attributed to a complex set of factors, including historical legacies, structural adjustment programmes and, most recently, Chinese investment. In many ways, external finance has helped African countries create jobs, increase productivity, and improve competitiveness, with recent achievements even in knowledge-intensive sectors such as business services and fintech. However, the region is currently facing its most severe phase of debt and fiscal distress in this century, precisely when it needs to mobilise resources to meet development objectives and climate commitments. While Africa’s hard-won credit market access had been hailed as the key to boosting the region’s growth and development, countries now face significant challenges in their relationship with international capital, with profound economic, political and social implications. Despite tensions, China and the West share a common interest in helping African nations address their mounting debt problems and will need to step up their efforts to find a mutual understanding. The G20 must aid this process by supporting debt relief initiatives, coordinating debt restructuring efforts and working with the African Union to address underlying issues.

- The Challenge

In recent years, many analysts have pointed to China’s capital expansion in Africa to explain the region’s growing economic challenges, arguing that its “debt-trap diplomacy” has pushed countries towards insolvency.[1] However, the reality is that African nations have long had a complicated history with international capital, as evidenced by their difficult relationships with traditional institutional lenders such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB), as well as with private international creditors.

For example, during the 1980s and 1990s, the IMF and the WB provided conditional lending to many African nations in the form of structural adjustment programmes (SAPs), which offered debt relief in exchange for economic policy adjustments. At the time, these were hailed as the key to restructuring the region’s productive capacity, with huge potential to “increase efficiency and restore growth” across the continent.[2] However, while SAPs initially aimed to address the challenges facing these emerging economies and contribute to Africa’s sustainable development, the academic literature generally agrees upon the ultimate ineffectiveness of these programmes, which have been widely condemned for their negative impacts on social welfare and economic growth.[3]

Consequently, many African economies started to turn to China for international finance, which generally offered loans with fewer strings attached and was willing to lend to authoritarian governments that the West frowned upon.[4] Beginning in the early 2000s, Chinese lending in resource-rich African countries expanded rapidly, with oil- and other mineral-backed infrastructure projects spreading across the region, particularly within the framework of the country’s global infrastructure development program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The lack of transparency in these arrangements, however, makes it hard to assess the extent of economic development enabled by Chinese capital, though widespread concerns about large-scale corruption and mismanagement seem to point to a missed opportunity.[5]

Hence, while traditional institutional lenders have been criticised for their focus on fiscal austerity and economic liberalisation, China’s approach to lending in Africa has been condemned for its lack of transparency and accountability, as well as for its support for corrupt and authoritarian regimes. Both China and the West, have an important role in promoting Africa’s sustainable development, but there is a dire need for greater cooperation and coordination. The US and China are currently engaged in a debt standoff that will only hurt poor nations in the long run, so differences stemming from geopolitical tensions should be put aside for the emergence of effective solutions.[6] But how did the continent find itself in its current conundrum? And, more importantly, what can G20 countries do about it?

Top of FormBottom of Form

Africa’s foreign debt problems have been mounting since 2014, when global oil prices fell sharply and a first group of countries began to struggle servicing their debts. In response, international capital moved quickly from financing infrastructure projects to buttressing economies against the impacts of resource dependence and bad governance, hoping to buy time until commodity prices stabilised.[7] However, these were unable to ease pressure on indebted sovereign governments, and now, these challenges have been compounded by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the steep hike of interest by the US Federal Reserve.[8]

At the end of 2020, the region’s external debt stood at almost US$700 billion, with some 12 percent owed to Chinese lenders.[9] China did not create Africa’s problems, but it does have an important role to play in helping countries return to a path of debt sustainability. According to the latest IMF data, out of 70 countries facing debt problems, 40 are in Africa, with nine of them, including Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe, already in what is considered “debt distress” and another 13 at “high risk” (See Table 1).[10]

Table 1. IMF List of African Countries at Risk of Debt Distress

| Country | Risk of debt distress |

| Benin | Moderate |

| Burkina Faso | Moderate |

| Burundi | High |

| Cameroon | High |

| Cabo Verde | Moderate |

| Central African Republic | High |

| Chad | High |

| Comoros | High |

| Congo, Democratic Republic of | Moderate |

| Congo, Republic of | In debt distress |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Moderate |

| Djibouti | High |

| Ethiopia | High |

| Gambia, The | High |

| Ghana | In debt distress |

| Guinea | Moderate |

| Guinea-Bissau | High |

| Kenya | High |

| Lesotho | Moderate |

| Liberia | Moderate |

| Madagascar | Moderate |

| Malawi | In debt distress |

| Mali | Moderate |

| Mauritania | Moderate |

| Mozambique | In debt distress |

| Niger | Moderate |

| Rwanda | Moderate |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | In debt distress |

| Senegal | Moderate |

| Sierra Leone | High |

| Somalia | In debt distress |

| South Sudan | High |

| Sudan | In debt distress |

| Tanzania | Moderate |

| Togo | Moderate |

| Tonga | High |

| Uganda | Moderate |

| Yemen, Republic of | Moderate |

| Zambia | In debt distress |

| Zimbabwe | In debt distress |

Source: IMF, 2023

Indeed, the challenge is paramount, and this has also been acknowledged from the Chinese side. A recent report noted that as “Africa faces over US$100 billion worth of bonds maturing between 2023 and 2025, a debt and liquidity crisis is looming over the continent.”[11] Countries that are unable to refinance their debt “could slip into a downward spiral of defaults, credit rating downgrades, shortages in foreign exchange reserves and currency devaluation”, with profound consequences for the broader population.[12] The fear of contagion makes the risk of just one country defaulting already problematic, so all parties will have to make their contributions.

To be fair, beyond the external shocks caused by COVID-19, the war in Ukraine and the steep hike of the Fed, some countries have fallen into debt crises partly due to their own negligence. According to UNCTAD (2022), weak tax systems, high corruption levels and the failure to diversify exports[a] have contributed to persistently low revenue generation and made it difficult to service external debts. Many governments have also taken on debt with unfavourable terms, including high interest rates, short repayment periods, and restrictive covenants that have further exacerbated these complex, multifaceted issues.[13]

Yet finger-pointing will not make the issue go away. The reality is that African countries will need to reach agreements with their public and private international creditors, and that will likely involve providing new loans. However, several African countries have now lost access to international capital markets. Eurobonds, in particular, which had played a crucial role in many economies’ success stories, seem all but dried up, as private lenders have largely abandoned the continent and are now negotiating haircuts of up to 30 percent. Ghana offers perhaps the most compelling case. Despite great advances enabled by foreign capital, the country lost access to international markets in 2022 and has increasingly resorted to borrowing domestically, with interest rates of up to 30 percent that have further aggravated the risk of default and forced the central bank to step in to provide emergency funding.[14]

The case of Zambia is also a harbinger of things to come. The country defaulted in 2020 and was close to reaching an agreement with its lenders in 2022, but while China, which holds one-third of its external debt, initially agreed to restructure and take on losses, it is now asking for the involvement of multilateral development banks (MDBs) in the haircut, which Westerns lenders have bluntly opposed due to their preferred status. The stand-off continues, with several African countries now siding with China in calling for the MDBs to accept cuts.[15]

All in all, the case of Africa’s debt problems is a testament to the complex nature of debt sustainability challenges in the Global South, demonstrating how these issues can rarely be attributed to a single lender or country. A key problem is the overall lack of transparency, with some countries not disclosing the full extent of their debt or borrowing from non-traditional lenders, like China. This is not conducive to collaboration and makes the negotiations between the Paris Club and China even more difficult.[16] In any case, especially since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, debt restructuring efforts in Africa and beyond have been increasingly jeopardised by geopolitical tensions between the US, its allies, and China.[17] The politicisation of Africa’s debt negotiations will only make matters worse, so differences will need to be put aside to help countries achieve their economic recoveries and go back to investing in key areas such as education and health. We need a new approach to cooperation on debt and investment in Africa, and the G20 must lead this effort.

- The G20’s Role

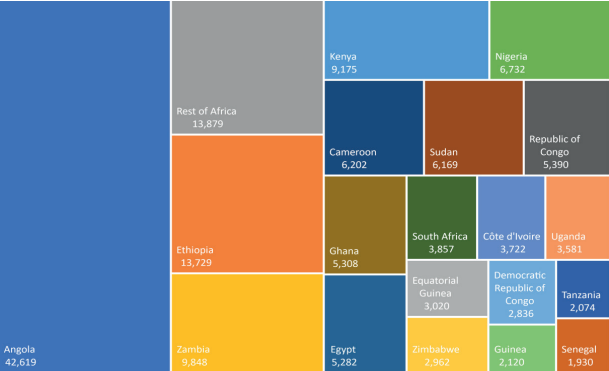

As we have seen, Africa’s debt challenges are a complex matter, with every country having its own specificities and an increased number of both public and private creditors involved, making debt restructuring processes—already difficult and messy—even more complicated to accomplish (see Figure 1). This is precisely why the G20 forum, along with its workgroups, is the perfect platform to increase cooperation on debt and investment. Its high technical and organisational capacity has already been leveraged for numerous debt relief initiatives, so there is already a lot to build from.

Figure 1: Top 20 Recipients of Chinese Loans in Africa, 2000–2020 (US$ millions, unadjusted)

Source: Vines, Butler, and Yu, 2022[18]

However, until now, the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and its successor programme, the Common Framework for Debt Treatments (CF), have both been broadly limited when it comes to immediate and long-term external debt restructuring. The DSSI did see relative success during the worst days of the pandemic, granting much-needed debt payment suspension to poor countries that suddenly came at the risk of defaulting on their debts. But the initiative was short-lived and soon succeeded by the hitherto unsuccessful CF. The new initiative has been needlessly based on the Paris Club, even though these countries only represent a fraction of developing countries’ total creditors, leaving private creditors outside of the negotiations and without a say in the restructuring processes. Additionally, the G20 has attached harsh conditionality requirements that make it difficult for countries to access the initiative. According to the IMF, by December 2021, only three African countries had applied to the framework—Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia—but so far none have been able to achieve successful debt restructuring.[19] More recently, Ghana has also called for assistance under this framework.

Looking forward, G20 members will need to show resolve and remain committed despite their differences. They must learn to work with non-G20 countries and other actors, such as MDBs and private creditors, to ensure that African countries receive the debt relief they desperately need. They could also help link debt restructuring efforts to development goals and climate commitments, making the most of available synergies to help countries embark on a journey of sustainable, inclusive recoveries. Further, their assistance should be aimed at enabling the region to address the root causes of its escalating debt burden. In the following section, we propose a series of recommendations to help the G20 be more effective in its future endeavours.

- Recommendations to the G20

Cooperation for debt relief

The G20 and Paris Club countries must work together with China and the African Union on comprehensive measures to alleviate countries facing debt crises. For example, a recent deal between Ghana’s official creditors demonstrated the potential of co-chaired committees to solve impasses and negotiate on equal terms. The country was in desperate need of an IMF bail-out that had been blocked by the lack of assurances by Ghana’s bilateral creditors, but China and France finally agreed on a distribution of cuts in exchange for the WB providing additional grants and low-interest loans to Ghana.[20] The country has become the first to test such a compromise, but it could become a model for other economies in the region. The G20 should aim to facilitate similar exchanges and provide a framework for cooperation and coordination for future committees.

MDBs should get involved

Increasingly, many experts are calling for MDBs to be involved in debt restructuring negotiations.[21] The argument that they are preferential creditors and this would be impossible can be questioned by the fact that these same MDBs had provided debt relief in the mid-1990s—e.g., the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative—and in the late 2000s—e.g., the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative. A recent meeting between African finance ministers, for example, called on WB shareholders to increase the amount of low-interest money available to countries through its International Development Assistance fund and for the IMF to sustain its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust with additional funding.[22] G20 countries should provide the necessary guarantees to make sure that such initiatives do not disappear when they are needed the most, and that they get the appropriate funding to achieve their intended aims.

Private sector participation in the CF

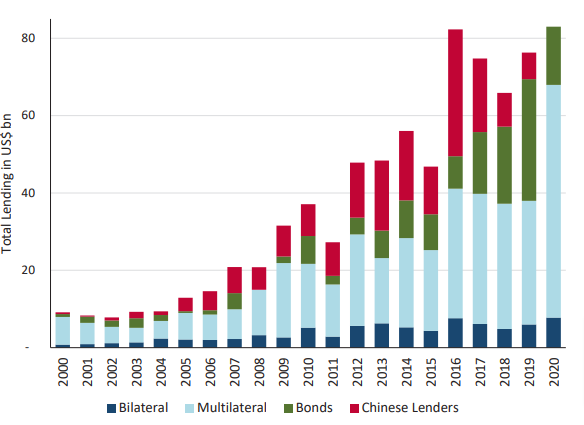

The CF does not currently provide for adequate participation of the private sector. It is based on the old Paris Club logic that public lenders will agree first and then the private sector will follow, which has been rendered obsolete now that creditors do not consist only of official lenders and major banks (see Figure 2). This is a shortcoming and it must be overcome, albeit more ambitiously than through collective action clauses that have only seen moderate success. The G20 must therefore overhaul the existing framework to allow for increased involvement of private sector actors in debt negotiation and forge new and more sustainable debt-relief talks. In turn, private creditors should be willing to participate in debt-service suspension talks and grant some level of debt-payment forbearance.[23]

Figure 2: Creditors Driving Africa’s Sovereign Debt Boom

Source: Mihalyi and Trebesch, 2023[24]

Linking debt relief to development goals and climate commitments

As proposed by the Global Development Policy Center, governments that benefit from debt relief should align their policies to the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and the Paris Agreement, and develop their own Green and Inclusive Recovery and Resilience Strategies.[25] The G20 should leverage its technical and organisational capacity and think of an ambitious agenda that will allow tackling Africa’s debt crisis while providing countries with the fiscal space they need to respond to their equally important sustainability crisis. It should then encourage countries with unsustainable debts to participate in debt restructuring talks and help orient relief efforts towards green, inclusive recoveries.

Expand the Paris Club or accept the African Union as a full member

The Paris Club is an informal group of 22 mainly rich Western countries that comprises the world’s historic, traditional lenders. However, there are now many emerging economies that have also become international lenders, whose participation has not been appropriately incorporated into existing forums. The Paris Club should therefore expand its membership, and include all G20 countries, for example, or perhaps we should find a new platform to resolve debt relief questions, for instance under the umbrella of the IMF. One interesting proposal would be for the G20 to consider incorporating the African Union as a full member to have more cooperation and coordination channels with African countries and involve them in future reforms of the global financial architecture.[26]

Debt sustainability

The G20 should also work with African countries to build resilient strategies. This could be done by developing frameworks for the short and medium term that allows African countries to balance the investment in economic development with the commitment to fiscal stability. This concerted effort would provide nations with more access to financial resources and technical support to manage their debt. Here, the G20 could draw lessons from the Bridgetown Initiative, an action plan that aims to unlock climate finance for low-income countries with new mechanisms and ambitious reforms.[27]

Enhance transparency

Right now, debt restructurings are messy arrangements because there is a lack of transparency that benefits holdouts and free-riders. Both creditors and debtors should be obliged to provide all relevant information to an international agency, perhaps located at the IMF. This information should include all loans, covering amounts, terms, guarantees, assurances and more. In the long run, this transparency might improve the lending process and the fiscal policy of the borrowers. If the underlying problems that led to unsustainable debt are not analysed and tackled properly, they will persist in the future.

Support economic growth opportunities in debtor countries through trade

To address the underlying challenges of achieving debt sustainability, the G20 could support African countries by facilitating the removal of trade barriers and promoting trade agreements. The G20 forum is an excellent platform for coordinating global policies on trade, as evidenced by the recent success of its Trade and Investment Working Group (TIWG) in Mumbai.[28] By prioritising the integration of African countries into global markets, the G20 could help the continent create further economic opportunities.

Attribution: Miguel Otero Iglesias, Beatrice Grace Aluoch Obado, and Agustín González-Agote, “Increasing G20 Cooperation on Debt and Investment in Africa,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[a] The dependence in commodity exports, in particular, has been a major source of instability. Export revenues represent the main growth engines for many African economies but tend to be highly volatile. External factors, such as currency fluctuations, have historically amplified these effects.

[1] Faris Al-Fadhat and Hari Prasetio, “How China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy Works in African Countries: Evidence from Zimbabwe, Cameroon, and Djibouti,” Journal of Asian and African Studies, November 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221137673; Christoph Trebesch and Hannah Ryder, “Hidden Debts and Defaults: A Chinese Debt Trap for Africa?,” Kiel Institute for the World Economy, April 2023, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/institute/events/global-china-conversations/hidden-debts-and-defaults-a-chinese-debt-trap-for-africa/; “Debt Diplomacy: Is China Creating a “Debt Trap” in Africa?”, VOA Africa, January 26, 2023, https://www.voaafrica.com/a/6934531.html.

[2] Ishrat Hussain, “Poverty and Structural Adjustment: The African Case,” World Bank, September 1993, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/517231468741855925/pdf/multi0page.pdf.

[3] Nana Yaw Oppong, “Failure of Structural Adjustment Programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa: Policy Design or Policy Implementation?,” Journal of Empirical Economics, July 2014, https://ideas.repec.org/a/rss/jnljee/v3i5p6.html

[4] Alex Vines, Creon Butler, and Jie Yu, “The Response to Debt Distress in Africa and the Role of China,” Chatham House, December 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/12/response-debt-distress-africa-and-role-china.

[5] Salem Solomon and Casey Frechette, “Corruption Is Wasting Chinese Money in Africa,” Foreign Policy, September 13, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/13/corruption-is-wasting-chinese-money-in-africa/.

[6] Gabrielle Steinhauser, “Debt Standoff Between China and U.S. Hurts Poor Countries, Zambia’s President Warns,” The Wall Street Journal, April 10, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/debt-standoff-between-china-and-u-s-hurts-poor-countries-zambias-president-warns-3f34f762.

[7] Vines, Butler, and Yu, “The Response to Debt Distress in Africa and the Role of China.”

[8] Sara Pantuliano, Gregory Smith, Yunnan Chen, and Bright Simmons, “On Borrowed Time? The Sovereign Debt Crisis in the Global South,” Overseas Development Institute, March 2023, https://odi.org/en/insights/think-change-episode-22-on-borrowed-time-the-sovereign-debt-crisis-in-the-global-south/.

[9] Chinedu Okafor, “10 African Countries with the Highest Debt to China,” Business Insider Africa, March 2023, https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/lifestyle/10-african-countries-with-the-highest-debt-to-china/6zkd9nf.

[10] International Monetary Fund , “List of LIC DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries,” IMF, May 2023, https://www.imf.org/external/Pubs/ft/dsa/DSAlist.pdf.

[11] Tang Xiaoyang, “The Trap of Financial Capital: The Impact of International Bonds on the Debt Sustainability of Developing Countries,” Tsinghua University, August 2022, https://www.dir.tsinghua.edu.cn/iren/TrapofFinancialCapital.pdf.

[12] Xiaoyang, “The Trap of Financial Capital”

[13] UN Conference on Trade and Development, “Economic Development in Africa Report 2022,” UNCTAD, July 2022, https://unctad.org/edar2022.

[14] Adam Tooze, “Finance and the Polycrisis (6): Africa’s Debt Crisis,” Chartbook, December 2022, https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/finance-and-the-polycrisis-6-africas.

[15] Etsehiwot Kebret and Hannah Ryder, “China’s Debt Relief Position Is Actually Reasonable,” The Diplomat, February 22, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/02/chinas-debt-relief-position-is-actually-reasonable/.

[16] Lex Rieffel, “Normalizing China’s Relations with the Paris Clubm” Stimson, April 20, 2021, https://www.stimson.org/2021/normalizing-chinas-relations-with-the-paris-club/.

[17] Pantuliano, Smith, Chen, and Simons, “On Borrowed Time? The Sovereign Debt Crisis in the Global South.”

[18] Vines, Butler, and Yu, “The Response to Debt Distress in Africa and the Role of China.”

[19] Kristalina Georgieva and Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, “The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Must Be Stepped Up,” IMF Blog, December 2, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/12/02/blog120221the-g20-common-framework-for-debt-treatments-must-be-stepped-up.

[20] Christian Akorlie, Jorgelina Do Rosario, and Rachel Savage, “Ghana’s Official Creditors Pave Way for IMF Sign-off on $3 Bln Loan,” Reuters, May 12, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/ghana-creditors-committed-negotiate-debt-relief-paris-club-2023-05-12/.

[21] Kevin Gallagher, “History’s Solution to the China-US Debt Standoff,” China Global South Project, March 2023, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/analysis/historys-solution-to-the-china-u-s-debt-standoff/?s=08.

[22] Maura Leary, “African Finance Ministers Demand Action on Global Financial Architecture Reform,” African Center for Economic Transformation, April 2023, https://acetforafrica.org/news-and-media/press-releases/african-finance-ministers-demand-action-on-global-financial-architecture-reform/.

[23] Tim Adams, “IIF Statement Following the Conclusion of the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Virtual Meeting,” Institute for International Finance, April 2020, https://www.iif.com/About-Us/Press/View/ID/3856/IIF-Statement-Following-the-Conclusion-of-the-G20-Finance-Ministers-and-Central-Bank-Governors-Virtual-Meeting.

[24] David Mihalyi and Christoph Trebesch, “Who Lends to Africa and How? Introducing the Africa Debt Database,” Kiel Institute for the World Economy, April 2023, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kiel-working-papers/2022/who-lends-to-africa-and-how-introducing-the-africa-debt-database-17146/.

[25] Ulrich Volz, Shamshad Akhtar, Keving Gallagher, Stephany Griffith-Jones, Jörg Haas, and Moritz Kraemer, “Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery: Securing Private-Sector Participation and Creating Policy Space for Sustainable Development,” Global Development Policy Center, June 2021, https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2021/06/DRGR-Report-2021-FIN.pdf.

[26] Leary, “African Finance Ministers Demand Action on Global Financial Architecture Reform.”

[27] Kristine Liao, “Not Heard of the Bridgetown Initiative? What to Know About the Game-Changing Plan for Climate Finance,” Global Citizen, May 9, 2023, https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/climate-change-bridgetown-initiative-mia-mottley/.

[28] G20, “The First Trade and Investment Working Group Meeting Concludes in Mumbai,” G20, March 2023, https://www.g20.org/en/media-resources/press-releases/mar-23/tiwg-concludes/.