Task Force 7 – Towards Reformed Multilateralism: Transforming Global Institutions and Frameworks

Abstract

Existing global governance agreements and institutions do not cover all aspects of the climate crisis. New institutions have been added lately as subsidiary bodies; there are also informal arrangements, plurilateral agreements, and discussion groups working on climate directly or have incorporated it into their agendas. This Policy Brief argues that international climate governance must be redesigned to avoid fragmentation, overlaps, and divergent strategies. The G20 can play a leading role in convening, organising, and disseminating innovative models of climate governance. It can:

(a) Map functions and mandates of existing bodies, agencies, and structures related to international climate governance to prevent gaps and uncoordinated overlap;

(b) Suggest which bodies are most capable of planning and implementing the necessary efforts to meet climate goals;

(c) Identify paths for civil society participation; and

(d) Align G20 outcomes to the commitments of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

1. The Challenge

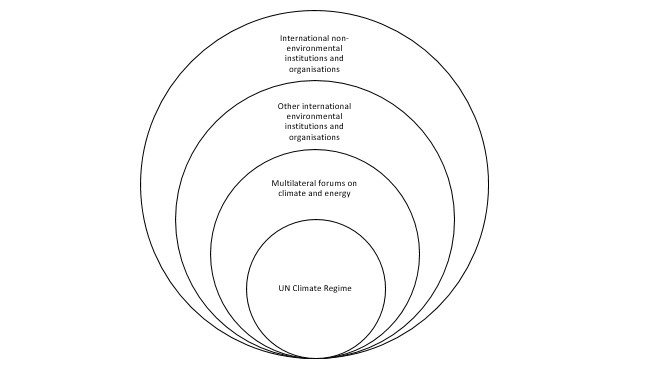

The governance architecture to combat climate change has progressively developed into a complex regime. As a result, it is showing signs of fragmentation and functional overlaps.[1] Encompassing institutions with different objectives, stakeholders, and priorities, global governance of climate change has an array of fragmented architectures. Some are synergistic, others cooperative, while still others are in conflict.[2]

This Policy Brief argues that climate change architecture is a mix of these three trends. At the core of the synergistic architecture is the centralising and organisational role of the UNFCCC. Proposed in 1992 and active since 1994, the UNFCCC is the foundational document of the international climate change regime. It does not contain legally binding emission targets, but it extends beyond procedures by establishing comparatively strong monitoring machinery, including detailed reporting requirements and international review.[3] It also functions as a ‘centre of gravity’ for other UN institutions that either respond to the UNFCCC or are mandated to cooperate with it.

The UNFCCC, however, is itself the first layer of challenges. Many analysts are increasingly suggesting that the current climate governance architecture is insufficient to support the 2015 Paris Agreement goals because some of these goals go beyond its mandate. The UNFCCC faces limits similar to those many other UN-related institutions do: a growing number of issues have progressively been included without necessary adjustments, such as the democratisation of decision-making processes.

The second layer of challenges includes the ever-growing diversity of actors operating on the climate change governance landscape. In recent years, many additional institutions have been set up as subsidiary bodies, informal arrangements, plurilateral agreements, and discussion groups working directly on reducing emissions or incorporating it in their agendas, which increases the complexity of climate governance.

Figure 1: Spheres of Institutional Fragmentation in Global Climate Governance

Source: Based on Zelli, 2011, p.258.

This level of fragmentation can lead to “forum shopping” by countries and competition to promote different approaches to climate change.[4] Actors choose their preferred policy arena based on its governing characteristics.[5] Another challenge is that alternative governance arrangements can be created as supply-driven rather than demand-driven: they can be set up because of political interests rather than a functional need. The fragmentation can also disperse political attention by offering multiple initiatives with overlapping functions and membership and be an obstacle to countries with limited resources and capacity to be simultaneously active in parallel forums.

To reduce overlaps, global initiatives should “launch less and implement more” and develop a more coordinated leadership.[6] Year after year, the international community creates new initiatives that duplicate efforts instead of filling the gaps. Figure 2 divides some of the main public, private, and hybrid climate initiatives by theme. While there is overcrowding in sectors such as urban climate action, there is only one initiative devoted to carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Figure 2: Climate Governance Institutions by Theme, as of 2016

Source: Widerberg; Pattberg; Kristensen, 2016, p. 18.[7]

2. The G20’s Role

This Policy Brief argues that governance must be redesigned to overcome dysfunctional fragmentation. The G20 can act as a collaboration enabler.

Usually climate change arrangements are analysed by their effectiveness (composition and resources), their legitimacy (inclusiveness and access to information), and institutional fit. This brief looks at the extent to which various global agreements are aligned with the UNFCCC norms and goals and their overlap with other initiatives.[8] Analysts have observed that the G20 is well-positioned to take initiatives in climate change governance. One analysis, by Widerberg and Pattberg, 2014, of the G20’s suitability on each of the three parameters is reproduced in Table 1, with five stars as the maximum score.[9]

Table 1: G20’s Suitability for Climate Change Initiatives

| Effectiveness | Legitimacy | Institutional Fit | |||

| Actors | Resources | Inclusiveness | Access to information | Institutional fit | Demand-drive |

| **** | ***** | ** | ** | *** | ***** |

Source: Adapted from Widerberg and Pattberg, 2014, p. 9.[10]

The G20 is high on effectiveness because of the nature of its membership. It comprises 19 of the world’s major economies plus the European Union (27 countries) comprising roughly 70 percent of world population, and accounting for 85 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and more than 80 percent of world trade flows. Many G20 countries still face domestic social and economic challenges; even so, the group is relatively solid, both in terms of members and available resources. By enhancing the G7 representation and providing a more comprehensive view of global governance, the G20 has narrowed the gap between rule makers and rule takers.[11] (It is another matter that the G20 has not yet effectively worked to promote democracy and democratic values among all its members.)

The G20 has a background of providing channels for collaboration with institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. It is simultaneously an actor and a network. It can coordinate national policies and support the implementation of international commitments at the domestic level. It can influence the policies of its members and outside partners, and encourage multilateral cooperation by setting principles and codes of conduct. It has the capacity to link issues and build issue-specific coalitions. Its 2009 agreement to phase out fossil fuel subsidies is one such example.[12]

The G20 also provides a forum to build mutual understanding among members. The current presidency country, its immediate predecessor and the following year’s successor form a troika, which works together not only at the government level but also at the level of engagement groups. It becomes an opportunity for concerted action and reinforcing of ties between countries that are not traditional partners. The G20 meetings are also enablers of bilateral and plurilateral meetings. Many agreements and collaborative endeavours have started at the margins of the G20’s activities.

As for institutional fit, the G20 confirms its commitment to the UNFCCC in almost every communiqué. Its score (five stars) on the ‘demand-driven’ sub-parameter relates to the fact that the G20 was created precisely to fill a governance niche and expand the G7/G8[a] grouping to incorporate emerging economies. At initial G20 summits, there was a divide between those countries that emphasised the group’s role in climate action and those which insisted that the UNFCCC was the appropriate forum. The traditional division between developed and developing countries also manifests itself in many G20 debates. However, a number of recent G20 initiatives show that, despite institutional flaws, the G20 has progressively included climate change in its agenda. The initiatives include:

- Climate change commitments: The G20 started to issue climate-related communiqués starting with its 2009 summit. Between 2009 and 2014, for instance, it made 49 climate commitments, mainly related to the Conference of the Parties (COP) on climate change, sustainable development, and climate finance.[13]

- Data Gaps Initiative (DGI): In cooperation with institutions such as the IMF, the G20 has supported data production. One of its pillars is producing and collecting reliable data for climate policies. It has, however, also recognised the challenges involved noting that “delivery will need to take into account national statistical capacities, priorities, and country circumstances, as well as avoiding overlap and duplication at the international level.”[14]

- Initiatives under the Finance Track: The G20 subgroup on the financial sector is looking at climate-related financial risks. Backed by data from the Financial Stability Board, it promotes discussions among G20 central banks’ leaders. The Finance Track also established the Green Finance Study Group (later called Sustainable Finance Study Group) to identify institutional and market barriers to green finance. Inputs are also being provided by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

- Initiatives under the Sherpa Track: All working groups under this track relate directly or indirectly to climate change and sustainability. In particular, it has the Energy Transitions Working Group (ETWG) and the Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group (CSWG). The former, previously called the Energy Sustainability Working Group, has been pivotal to the debates around reducing subsidies for fossil fuels. Its partners included the IMF, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the International Energy Forum (IEF), the World Bank, and the OECD. It supported the publication of the G20 Principles on Energy Collaboration, a document that commits G20 members to enhance coordination on energy access, energy security, and sustainable development. The latter is mainly devoted to policies on the circular economy, resource efficiency, water management, and climate change. The groups meet periodically with the Environment Deputies Meeting (discussed below).

- Environment Deputies Meeting (EDM): Established in 2018, the EDM convenes conclaves of Environment and Climate ministers of G20 countries to exchange views and benefit from CSWG studies and reports. It issues communiqués on climate change and promotes joint workshops with CSWG.

- G20 Engagement Groups: These were formed to provide a consultation forum for non-government organisations (NGOs) from G20 member countries to meet regularly and draft proposals and recommendations for the G20. All such groups touch upon climate change at some level, but the Urban20, the Business20, the Civil20, and the Think20 have made consistent contributions. At the time of publishing this brief, the third highest number of policy briefs produced by the Think20 (T20) group relate to climate.

Despite these achievements, scope for improvement exists. Many members have still not submitted stronger nationally determined commitments (NDCs). Indeed, there have even been some regressions. Most are yet to announce long-term strategies. Curbing greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement goals and overcoming the climate finance gap will be impossible without their commitment. The converse is also true. As the World Resources Institute noted in a 2021 report, “If all G20 members were to adopt mid-century net zero commitments and align their NDCs with a 1.5°C pathway, end-of-century global warming could be limited to 1.7°C.”[15] It would also generate positive externalities such as greater global prosperity, economic stability, energy access, and job opportunities.

Table 2: G20 Climate Commitments (as of 2022)

| Country | % of global GHE | Effect of updated NDCs | Long-term strategy | Net-zero target |

| Argentina | 0.8% | Enhanced mitigation | Not submitted | 2050 |

| Australia | 1.3% | Enhanced mitigation

|

Not submitted | 2050 |

| Brazil | 2.9% | Higher GHE emissions | Not submitted | 2050 |

| Canada | 1.6% | Enhanced mitigation | Submitted | 2050 |

| China | 23.9% | Not submitted | Not submitted | 2060 |

| European Union | 6.8% | Enhanced mitigation | Submitted | 2050 |

| France | Part of EU | Same as EU | Submitted | 2050 |

| Germany | Part of EU | Same as EU | Submitted | 2045 |

| India | 6.8% | Enhanced mitigation | Not submitted | 2070 |

| Indonesia | 3.5% | Enhanced mitigation | Submitted long-term low carbon and climate resilience strategy (LTS-LCCR) 2050 | 2060 |

| Italy | Part of EU | Same as EU | Submitted | 2050 |

| Japan | 2.4% | No change | Submitted | 2050 |

| Mexico | 1.3% | Higher GHE emissions | Submitted | No target set yet |

| Russia | 4.1% | Enhanced mitigation | Not submitted | No target set yet |

| South Africa | 1.1% | Not submitted | Not submitted | No target set yet |

| Saudi Arabia | 1.3% | Not submitted | Not submitted | No target set yet |

| South Korea | 1.4% | No change | Submitted | 2050 |

| Turkey | 1% | Not submitted | Not submitted | No target set yet |

| United Kingdom | 1% | Enhanced mitigation ambition | Submitted | 2050 |

| United States | 11.8% | Enhanced mitigation | Submitted | 2050 |

Source: Based on Climate Analytics, 2021, updated with data from UNFCCC, 2022.[16]

The G20’s flexible modus operandi is also an impediment. As the group does not have a permanent secretariat and each presidency can choose its priorities, it hinders the coherence of policy proposals. Although the troika, and the sherpa and the finance tracks, work to ensure continuity, the G20 is highly subject to exogenous international dynamics and political will. A recent example was its failure to agree on a climate communiqué at the 2022 Bali summit following differing perceptions of the Ukraine invasion and the US-China polarisation, even though the language of the disputed communiqué was built upon previous UNFCCC and COP agreements.[17] Some analysts also argue that the G20 is unlikely to drive more than piecemeal change unless it has unilateral state leadership or leadership from a coalition of states.[18] One of them, Christian Downie (2015), also points out that the G20 has historically functioned as a crisis committee responding to external shocks instead of a steering committee that produces global public goods.

3. Recommendations to the G20

The recommendations follow the four main objectives of this policy brief (as outlined in the Abstract):

(a) Map functions and mandates of existing bodies, agencies, and structures related to international climate governance to prevent gaps and uncoordinated overlap. Recommendation:

- The troika’s mandate should include enhancing coordination between existing governance structures, thereby avoiding the creation of fresh initiatives which may overlap with old ones. It would also prevent forum shopping by countries and ensure that governance is solutions-driven.

(b) Suggest which bodies are most capable of planning and implementing the necessary efforts to meet climate goals. Recommendations:

- The G20 is an apt forum to mobilise resources to overcome the finance gap.[19] Beyond public resources, the G20 has a strong network and experience in partnering with other funding institutions. Study groups under the finance track should determine quantifiable targets of resource mobilisation and the desirable balance between public and private capital for each G20 member.

- The G20 should keep a record of each member’s climate commitments and quantifiable targets for GHE reduction to meet the Paris Agreement goals. The DGI should not only collect, organise and systematise data but also indicate discrepancies and lack of transparency in national reports.

- The sherpa track would benefit from inputs of peers on proposed climate commitments before they are announced/launched. The G20 should urge countries to communicate concrete and measurable emission reduction targets and safeguard additionalities. If each country implements coherent and transparent reporting procedures, the G20 can avoid fake, exaggerated claims about climate gains (green washing/blue washing).

(c) Identifying paths for civil society participation. Recommendations:

- The G20 should establish a minimal set of expected procedures for systematic, high-level interaction between its finance and sherpa tracks and its official engagement groups.

- Recommendations from engagement groups that are entirely or partially included in G20 official communiqués should be transparently credited. This would enhance public awareness about the effectiveness of civil society participation. It will also show how seriously the G20 takes civil society suggestions. Engagement groups’ final reports could be listed as annexes in G20 communiqués.

- Organisations represented in the engagement groups should be allowed to participate in Working Group workshops to build capacity. The G20 could also help civil society organisations familiarise themselves with its priorities and modes of expression to better equip them in drafting recommendations. Their inclusion in EDMs and CSWG activities would also help.

- There should be strategies to finance engagement groups and enhance developing countries’ participation. As governance grows more complex, small NGOs from developing countries often face monetary constraints in attending too many meetings overseas and should be helped.

- The G20 could also consider including non-G20 countries as observers in engagement group activities. Climate change is not confined by national borders. This would promote consideration of regional challenges better and provide a wider platform for peer-to-peer learning.

- Existing Working and Study Groups should systemise cooperation with engagement groups to benefit from their work and avoid duplication.

- Each presidency should convene a transversal meeting on climate change with all engagement groups to coordinate recommendations and find common ground. Each group would still keep its autonomy, but it would help them avoid discrepancies and strengthen their chances of influencing G20 communiqués.

(d) Align G20 outcomes to the commitments of the UNFCCC. Recommendations:

- Using its experience of energy transition debates, the sherpa track, in close coordination with engagement groups, should draft the ‘G20 principles on climate change’, for endorsement at the next G20 summit.

- EDM participants should jointly meet the minister from the Finance Track, so as to go beyond the “climate bubble” and sensitise leaders to the urgency of combating climate change.

- The EDM should coordinate agendas and meet before each annual COP. It would promote initial exchange of ideas to identify common ground and inflection points which, in turn, would help in preparing for the COP meetings.

Attribution: Francisco Gaetani and Marianna Albuquerque, “Redesigning Climate Governance,” T20 Policy Brief, June 2023.

[a] These comprise the countries France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Canada, the UK, the US and Russia (in G8)

[1] Oscar Widerberg, Philipp Pattberg, and Kristian Kristensen, Mapping the Institutional Architecture of Global Climate Change Governance. Amsterdam: Institute for Environmental Studies, 2016.

[2] Frank Biermann, Fariborz Zelli, Philipp Pattberg, and Harro van Asselt, “The Architecture of Global Climate Governance: Setting the Stage,” In Global Climate Governance Beyond 2012. Architecture, Agency and Adaptation, eds. Frank Biermann, Philipp Pattberg, and Fariborz Zelli, 15-24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[3] Daniel Bodansky and Lavanya Rajamani, “Evolution and Governance Architecture of the Climate Change Regime,” In International Relations and Global Climate Change: New Perspectives, eds. Detlef Sprinz and Urs Luterbacher. Boston: MIT Press, 2016.

[4] Fariborz Zelli, “The Fragmentation of the Global Climate Governance Architecture,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2 (2011): 255-270.

[5] Hannah Murphy and Aynsley Kellow, “Forum Shopping in Global Governance: Understanding States, Business and NGOs in Multiple Arenas,” Global Policy 4, no 2 (2013):139-149.

[6] Jimena Leiva Roesch and Julia Almeida Nobre, Strengthening the Current Climate Governance System: Mapping Leading States and Initiatives. Stockholm: Global Challenges Foundation, 2021.

[7] Widerberg, Pattberg, and Kristensen. Mapping the Institutional Architecture of Global Climate Change Governance.

[8] Widerberg and Pattberg, International Cooperative Initiatives in Global Climate Governance: Solution of Thread?

[9] Widerberg and Pattberg, International Cooperative Initiatives in Global Climate Governance: Solution of Thread?

[10] Widerberg and Pattberg, International Cooperative Initiatives in Global Climate Governance: Solution of Thread?

[11] Andrews-Speed, Philip, and Xunpeng Shi, “What Role Can the G20 Play in Global Energy Governance? Implications for China’s Presidency,” Global Policy 7, no. 2 (2016): 198-206.

[12] See John J. Kirton and Ella Kokotsis, The global governance of climate change: G7, G20, and UN leadership. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2015.

[13]John J. Kirton and Ella Kokotsis, The global governance of climate change: G7, G20, and UN leadership.

[14]International Monetary Fund, “G20 Leaders Welcome New Data Gaps Initiative to Address Climate Change, Inclusion and Financial Innovation”, Press Release n. 22/410, November 28, 2022.

[15] Climate Analytics, Closing the Gap: The Impact of G20 Climate Commitments on Limiting Global Temperature Rise to 1.5 °C. World Resources Institute, 2021.

[16] UNFCCC, “NDC Registry”, accessed June 2, 2023.

[17] Kate Lamb and Yuddy Cahya Budiman, “G20 climate talks in Indonesia fail to agree communique,” Reuters, August 31, 2022.

[18] Christian Downie, “Global Energy Governance in the G-20: States, Coalitions, and Crises,” Global Governance, 31, no. 3 (2015): 475-492.

[19] Promit Mookherjee, ed., Bridging the Climate Finance Gap: Catalysing Private Capital for Developing and Emerging Economies. New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation, 2023.