Task Force 6: Accelerating SDGs: Exploring New Pathways to the 2030 Agenda.

Abstract

Gender pay gap (GPG) is a complex issue that various forums, including the G20, have attempted to discuss. Mitigating GPG requires large-scale transformative changes, but constraints on financial resources and public spending, along with cultural norms and deep-seated societal beliefs, make it a difficult task. Proposed actions, therefore, must be economically prudent and actionable. This Policy Brief offers five recommendations for the G20 to help bridge the gender pay gap. These include: introducing pay transparency legislation; mandating data-driven gender budgeting; increasing emphasis on parental leave; promoting women in STEM subjects; and engaging with the industry by proposing initiatives such as exclusive women-only portals, reporting on gender, facilitating leadership programmes, and ‘de-biasing’ organisations. These proposals can help policymakers move the needle on gender equity, promote social justice, and improve economic outcomes.

1. The Challenge

Gender Pay Gap and its implications

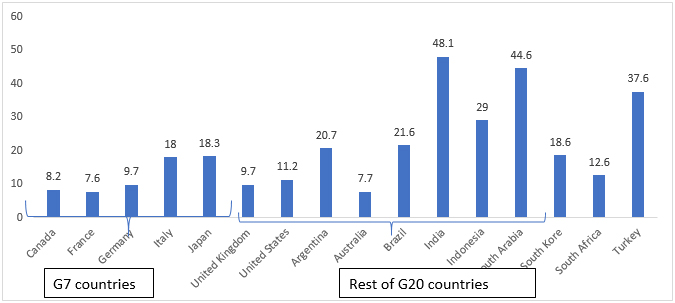

Gender imbalance in employment plagues women across the world. One such form of inequity—i.e., Gender Pay Gap (GPG)—relates to economic disparity due to gender. GPG is expressed as a percentage value and is calculated as “the difference between median earnings of men and women relative to median earnings of men.”[1] Globally, on average, women earn about 20-percent less than men,[2] though the rate varies across countries. While the gap has narrowed over time, it persists. (See Figure 1 for the gaps in the G20.)

Figure 1: Gender Pay Gap in G20 countries

Indicators of Gender Inequality in Employment

a. Labour Force Participation Rate and Job Gaps

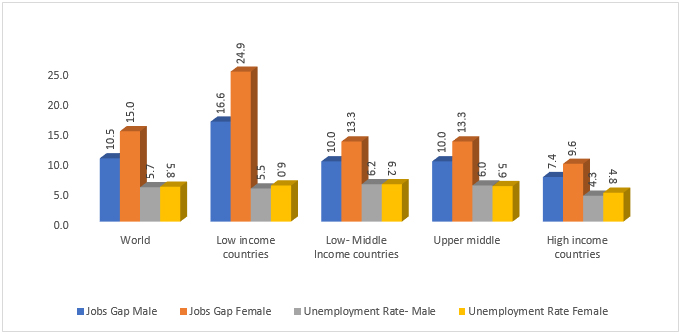

Examining labour force participation rate (LFPR) gives a snapshot of gender inequality in employment. Globally, the LFPR for men and women is 72.3 percent and 47.4 percent, respectively.[5] While a gap in LFPR between genders exists in all G20 countries, it is particularly significant for the non-G7 countries in the G20 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Gender Gap in LFPR (as percentage points)

Source: ILOSTAT, ILO modelled estimates, 2021[6]

Figure 3: Jobs Gap and UR for Men and Women, 2022

Source: ILOSTAT, 2022[8]

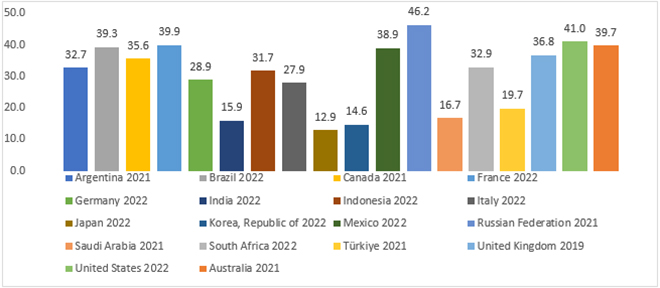

Inequities are also caused by stereotyping of gender roles. Globally, working women tend to give up on employment due to childcare responsibilities.[9] In addition, structural barriers and societal biases around gender roles result in women dominating low-paying and part-time jobs. Their representation in management positions remains low (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Proportion of Women in Managerial Positions in G20 Countries (%)

Source: Data sourced from ILOSTAT, ILO modelled estimates[10]

c. Lack of pay transparency

Pay transparency pertains to disclosures made about pay. Nearly half of the OECD countries (including some of the G20 countries) mandate pay transparency (Frey, 2021) but there is variation in implementation of such measures (see Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of OECD Countries with Pay Reporting/Auditing Regulations for Private Sector Companies

| Level of Pay Reporting | Countries |

| Countries that require companies to conduct regular pay audits, including reporting gender disaggregated pay | Canada, Finland, France, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden |

| Countries that require companies to report gender-disaggregated pay information without broader audit | Austria, Australia, Belgium, Chile, Denmark, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, United Kingdom |

| Countries requiring companies to report non-pay gender disaggregated information | Germany, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, United States of America |

| Counties in which pay audits are conducted to assess gender wage gap ad hoc within selected companies- | Costa Rica, Greece, Turkey, Ireland |

| No reporting requirements in place | All the remaining countries in the world. |

Source: Frey 2021 [11]

For instance, France requires employers to report on GPG metrics and commit to fixing it within three years.[12] Non-compliance is subject to penalties. Meanwhile, in Canada, companies with 10 or more employees are required to publish an equity plan and mandatory pay audits.[13] Other G20 countries like Mexico and India have ‘equal pay’ laws but no GPG reporting regulations. Appendix 1 shows that only some of the G20 have introduced reporting regulations. The disparity between countries is not surprising as pay transparency is a comparatively new policy instrument.

Mandatory reporting of GPG can expose gender inequity by providing access to information to the public and employees. Available evidence shows that mandatory pay gap reporting and the cost of potential reputational damage spurs organisations to take action to bridge the gender gap (Cowper-Coles et al., 2021).[14] Given the focus of G20 on fixing gender imbalances, legislation on pay transparency by member countries can help spearhead change.

d. Lack of prioritisation of gender issues in budgeting

Gender budgeting (GB), also known as gender-responsive budgeting, involves reviewing the potential impact of budget and public spending on reducing gender inequality. While gender-based fiscal policies and welfare schemes are an important focus area for all G20 countries, their review and auditing is minimal and the overall progress on GB has been variable (see Figure 5). The challenges in implementation also relate to the lack of sufficient gender-related data, making it difficult to track progress (UN Women Brief, 2018).

Figure 5. Commitment of G20 Countries to Gender Budgeting

Source: Gender Budgeting in G20 countries (IMF working paper)[15]

Across the world, women are seen as the primary caregivers in households. The World Values Survey Wave 7[16] found that people in developing countries overwhelmingly agree that “children suffer when the mother is working for pay.” This cultural assumption affects women’s LFPR. Women pay ‘wage penalty’ due to taking career breaks for motherhood (or ‘motherhood penalty’). In developed countries, women tend to take on part-time jobs to manage caring commitments, but in developing countries, women are more likely to drop off the labour market altogether.[17] The proportion of time women (including working mothers) spend on unpaid care work/household responsibilities is much higher than the male members in the family (UNDP, 2015).[18] Lack of childcare facilities also holds women back from working, both in developed and developing countries. To be sure, there are countries like those in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, where ‘motherhood penalty’ is low as childcare is a shared family responsibility. This diversity in challenges underscores the need for country-specific leave policies for working mothers.

G20 countries have enforced legislation on maternal/paternal/parental leave and made investments to address childcare (see Appendix 1). Yet the uptake remains low due to stereotypical assumptions of gender roles and concerns about the quality of childcare.

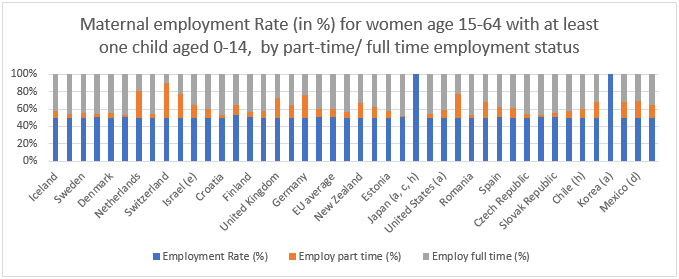

A 2018 UNICEF[19] report found that supporting women through offering childcare facilities can positively impact maternal employment. Figure 6 shows the maternal employment rates of OECD countries and illustrates how countries that have implemented policies such as paid maternity leave, childcare leave, subsidised childcare, and flexible work schedules have higher LFPR. Providing public-sponsored facilities for childcare may not be financially feasible for all the G20 countries. Yet, given the economic benefits of higher LFPR in the form of increased GDP and tax contribution, paid or subsidised childcare may be treated as long-term investment by governments. Providing infrastructure, and ‘accessible, affordable and good quality’[20] public care services, can have a positive impact on redistributing unpaid care work and freeing women’s time, thereby increasing female LFPR.

Figure 6: Maternal Employment Rates, OECD Member Countries

Source: OECD Family Database [21]

Note: No information about full-time/part time work is available for Japan and South Korea

2. The G20’s Role

Gender pay gap is an important issue across the G20 member countries and has been discussed in several previous summits. Individually, the G20 countries have implemented mechanisms for tackling gender imbalances, albeit in varying degrees. For instance, India has implemented a number of policies[22] that aim to address gender inequities, such as the Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao Scheme and Ujjwala. The G7 have all introduced measures to reduce GPG, but financial constraints on spending on social welfare have meant that the G20 countries vary in their efforts to a significant degree. Indeed, the World Economic Forum report[23] on global gender gap suggests that it will take another 132 years to close the gap.

Given how the G20 is home to two-thirds of the world’s population and 85 percent of global GDP, increasing female LFPR by at least 25 percent by 2025, can contribute to an increase in GDP of about 3.9 percent or US$5.8 trillion. This could raise the purchasing power of entire families, and thereby overall consumer spending.

India adopted the theme of “One Earth. One Family. One Future” for its G20 presidency, and declared that its tenure would prioritise women-led development.[24] There is an acknowledgement that progress on achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of Gender Equality (SDG5) and providing Decent Work and Economic Growth to all (SDG8), will only be achieved through decisive action on tackling GPG.

3. Recommendations to the G20

This Policy Brief offers recommendations that can potentially galvanise governments to bridge the gender wage inequity. G20 is an aggrupation of very diverse economies, and in the emerging and developing countries, there is a pronounced dominance of the informal economy where gender pay gaps are higher. The percentage of informality ranges from 88 percent for India to 47 percent for Brazil.[25] The informal sector limits enforcement of legal measures due to the absence of monitoring. The recommendations made in the following sections consider the complex nature of the informal sector.

a. Implementation of Pay Transparency Legislation

Governments must engage with industry and other stakeholders such as educational institutes, research centres, women’s groups, and employee associations before enforcing pay transparency legislation. Member countries can commit to country-specific targets, but the level of transparency mandated by law, must reflect contextual realities. In countries with no existing disclosure regulations, the implementation could be multi-staged. First, voluntary reporting can be encouraged, which can be followed by mandatory reporting where listed companies of a certain size (such as those with more than 250 employees) are mandated to annually disclose gender pay inequity information in the public domain. The regulation can be rolled out to smaller organisations in the next phase. Experience from countries that have implemented pay transparency measures shows that simplifying the process of reporting and making it technology-driven is critical in ensuring compliance.

For countries that have already implemented pay transparency regulations, the next step would be to mandate employer accountability through action plans. Employers in these countries can also be required to provide granular data on the pay gap. Further, employers and industries with persistent GPG can be mandated to conduct pay audits and ensure implementation and monitoring of equal pay law.

In countries with a dominant informal sector, it is likely to be difficult to track data on pay gaps. This can be resolved by digitising data from the informal sector—indeed, this has been on the agenda of the G20 since 2018 during Argentina’s G20 presidency.[26] In India, for instance, data on informal sector workers is being digitised through the e-Shram portal,[27] a self-reporting portal where workers register themselves. This dataset can capture pay and industry details and can be used to ascertain the degree of pay gap. Data can also be collected by academic agencies, and by industry councils for the different sectors in the economy.

b. Data-driven Gender Budgeting

G20 countries must develop and agree on indicators in GB on gender equality. They can gather gender-related data on an ongoing basis so that gender can be mainstreamed into policymaking. This can enable capturing data at source and leveraging statistical modelling and analytics to compare with benchmark data on a continuous basis. Such benchmark data needs to be made publicly available to enable G20 governments to collaborate with each other. Regular monitoring of databases will enable governments to track progress and monitor actual spending against planned expenditure on gender equality initiatives.

c. Implementation of parental leave policies and paid/subsidised childcare

Measures can include the following:

- Encouraging organisations to introduce shared parental leave (including leave to care for sick young children with short-term or chronic illness), which will allow parents to take leave in a flexible way and provide women an opportunity to return to work after the birth of a child.

- Financing an evaluation and review of current provisions to identify bottlenecks in their uptake.

- Investing in subsidised or state-funded childcare, in the form of nurseries for preschoolers and wrap-around care for primary school children.

The above-mentioned recommendations may be more suitable for the formal sector. For the informal sector, governments can introduce state-funded or subsidised childcare or childcare centres. In India, for example, the Anganwadi[28] scheme was introduced to combat malnutrition in children by providing free food at state-designated centres. These centres can be used as government-funded/subsidised childcare spaces for women in the informal sector. Given how such schemes tend to be resource-intensive, small pilots can be run to assess effectiveness.

d. Increased efforts on representation of women in STEM

Globally, women are underrepresented in high-paying STEM careers (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). Even though both young male and female students may show similar proficiencies in mathematics and science subjects, women’s confidence in taking up STEM careers reduces over time, due to social conditioning. Several G20 countries have implemented measures to encourage more women into STEM. For instance, beginning in 2018, the Indian government added a supernumerary quota of 20 percent for women in government-aided education institutions. The UK and the EU are promoting greater participation through mentoring and networking events.

G20 countries need to make STEM subjects and occupations more accessible to females. This can be done by:

- offering government-funded, merit-based, women-only scholarship schemes;

- encouraging industry to offer flexible working hours in STEM occupations, where possible;

- mandating all schools to provide career counselling to female pupils as part of the education policy;

- facilitating industry to organise women-only professional networks;

- collaborating with schools and universities and running talent spotting competitions; and

- running exclusive job portals for women in STEM.

e. Working with industry associations and organisations

The recommended initiatives given in the previous sections are not a panacea. Real change will come not only from mandating measures but by taking a holistic approach that protects women against discrimination and entrenched biases and supports them to progress in their careers. This requires working closely with industry associations and local governmental bodies. Some proposals are discussed in the following points.

- Introducing exclusive women-only job portals and encouraging industry to hire from those. These portals can be advertised in schools and universities through career counselling and media channels including LinkedIn.

- Encouraging reporting on gender-based outcomes. Large organisations across the world report their initiatives on social responsibility. Encouraging voluntary reporting on expenses earmarked and incurred on women’s development in the form of education, empowerment, health and employment opportunities will help increase employer accountability.

- Supporting women to take on positions of responsibility by introducing targeted leadership coaching and mentoring schemes. Governments can facilitate action by funding industry associations to run such programmes.

- Tackling unconscious biases by ‘de-biasing organisations’ (Bohnet, 2018).[29] This can be done by mandating gender-neutral job advertisements, encouraging blind recruitment to ensure that applicants are shortlisted irrespective of their gender, and introducing salary history bans.

Many of the policies suggested in this Policy Brief have been implemented, at least partially, in certain G20 countries. However, implementation continues to be a challenge. The brief has therefore focused on how these policies can be implemented so that they are more likely to reach a critical mass of compliance.

Attribution: Sumita Ketkar, Roma Puri and Sahana Roy Chowdhury, “Bridging the Gender Pay Gap,” T20 Policy Brief, May 2023.

Appendix 1

Regulations on Gender Equity in G20 countries

This table is based on following sources:

- Frey, 2021 (OECD)

- ILO Report, 2022[30]

Endnotes

[1] “Understanding the Gender pay gap,” International Labour Organisation, February 6, 2020.

[2] “The Gender Pay Gap,” International Labour Organisation, last modified, December 2022.

[3] “Statistics on Wages,” International Labour Organisation, accessed May 11, 2023

[4] “Understanding the Gender Pay Gap: Definition and Causes,” EU Monitor, April 12, 2023.

[5] “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2022,” International Labour Organisation. Geneva: International Labour Office, January 17, 2022.

[6] “Statistics on Employment,” International Labour Organisation, accessed May 11, 2023.

[7] “World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2023,” Geneva: International Labour Office, January 16, 2023.

[8] “Statistics on unemployment and labour underutilization,” International Labour Organisation, November 2022, accessed May 23, 2023.

[9] “Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work,” International Labour Organization, June 28, 2018.

[10] “Statistics on unemployment and labour underutilisation,” ILOSTAT, 2022, accessed May 11, 2023.

[11] Valérie, Frey, “Can pay transparency policies close the gender wage gap?” Pay Transparency Tools to Close the Gender Wage Gap, OECD Publishing, Paris. November 2021.

[12] “Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work.” International Labour Organization

[13] Overview of the Pay Equity Law, Employment and Social Development Canada, modified on January 27, 2023.

[14] Cowper-Coles, Minna, Miriam Glennie, Aleida Mendes Borges, and Caitlin Schmid. “Bridging the gap? An analysis of gender pay gap reporting in six countries,” October 2021.

[15] “Gender Budgeting in G20 countries,” IMF Working Paper, November 12, 2021.

[16] C. Haerpfer et al. (eds.). 2022. World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country-Pooled Datafile Version 5.0. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. doi:10.14281/18241.20

[17] “Spotlight on Work Statistics n°12,” International Labour Office brief, March 2023.

[18] Chopra Deepta and Krishnan Meenakshi, “Linking family-friendly policies to women’s economic: An evidence brief,” UNICEF, July 2019.

[19] “Gender Equality-Global Annual Results Report 2018,” UNICEF, 2018.

[20] Gromada, Anna, and Dominic Richardson, “Where do rich countries stand on childcare?” UNICEF Office of Research–Innocenti, 2021, accessed May 22, 2023.

[21] OECD, “LMF1.2. Maternal employment rates,” Family Databases, updated November, 2020.

[22] Women Empowerment Schemes. Ministry of Women & Child Development, accessed May 11, 2023.

[23] “Global Gender Pay Gap report,” World Economic Forum, July 13, 2022.

[24] Priyanka Tina Cardoz, “Women-led Development – India’s Opportunity at G20,” Invest India, January 18, 2023.

[25] Statistics on the informal economy – ILOSTAT, accessed May 14, 2023.

[26] “Digitisation and informality: Harnessing digital financial inclusion for individuals and MSMEs in the informal economy,” G20 Policy Brief, 2018.

[27] eShram, Ministry of Labour and Employment. Government of India, accessed May 14, 2023.

[28] “Anganwadi services,” Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India, accessed May 14, 2023.

[29] Iris Bohnet, “What works,” Harvard University Press, 2016.

[30] Annick Masselot and Martha Ceballos, “Pay transparency legislation: implications for employers’ and workers’ organizations,” International Labour Organisation, June 21, 2022.